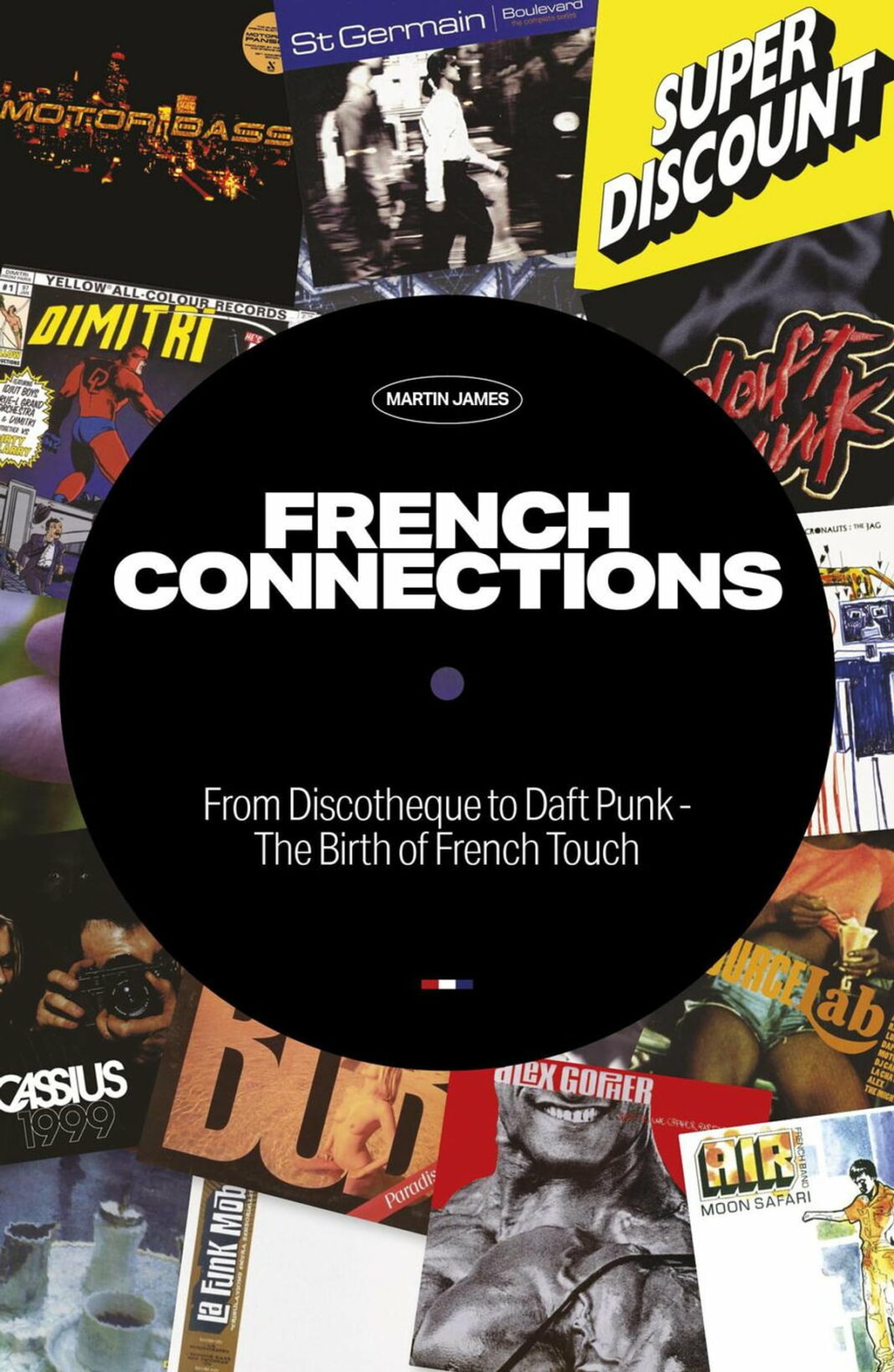

The book French Connections provides a comprehensive look at the French dance culture in its making. The empirical data of the book is comprised of interviews with important figures in French electronic music history and a range of sources as well as Martin James’ own experiences as an insider of the French dance music scenes. He himself coined the term “French Touch,” which is not only a genre-like definition of French dance music emerging in the second half of the 1990s but also an allusion to the rising French impact on the international dance music culture. Whereas artists like Daft Punk, Air, and Bob Sinclair were the main actors behind French Touch, James acknowledges that their music was the result of the experiments in the electronic music production of preceding decades.

The train of time that leads us to French Touch has many stops: From discotheque culture to musique concrete; from experiments with Ondioline and Moog to rave culture and techno parades. Every stop has its own places to visit and songs to hear, sometimes with their makers narrating their own journeys.

While the discotheques of the Second World War provide the historical context of the French relation to dance music, musique concrete acts as a source of a new sound aesthetic achieved by imaginative musical structuring and tape editing. Musique Concrete’s experiments with recorded sound, then, evolve into electro-pop, especially when Jean-Jacques Perrey combines the found sound with the Ondioline and the Moog synthesizers and “pushes the boundaries of electronic music for over four decades.” The way leading to the current electronic music scene in France branches off when it comes to techno, rave, and what Martin calls the French Touch. Defined as the French version of house music, French Touch blossoms at the backdrop of the government’s condemnation of the raves and as a closer relative to indie and hip hop cultures than rave and techno.

Spotify Playlist

Excerpts from the Book

French Hiphop & Techno

Nowhere was this more evident than in Paris, where the city’s urban projects were quickly turned into ghettos that seemed a million miles removed from the bourgeois affluence of Versailles. Surprisingly a government directive also aided the growth of hip hop in France. In a move aimed at slowing down the cultural homogenisation created by the spread of US concerns like McDonald’s, the French government imposed a limit on the amount of non-French language music allowed to be played on the radio. Although French pop quickly fit into this, airplay was also accessible to hip hop artists rapping in French. As a result, the words of artists like MC Solaar, NTM and Iam were quickly spread throughout the country. Philippe Zdar, who worked extensively with MC Solaar at this time, considers this to be the most important turning point for French music culture. “Hip hop was the key thing in French Touch because when NTM, Solaar, Iam, the other first bands who were successful, came up, it changed everything,” he explained. “In England, you were OK because you’d always had a lot of bands, but in France there was nothing. Just pop music for years and years. A few good ones, OK, but a lot of shit. So with hip hop, it was the first time that music was done by kids in France. “Hip hop was a great emancipation in music. It was the first time that people were able to make music in small studios and put it out on small labels. Suddenly kids were getting samplers and they could do it for themselves. And at the same time, the kids from the suburbs could speak about their lives with the rapping.” The success of hip hop in France was unparalleled in any other country in the world. With other territories unable to find their own voices in the face of American domination, the French rappers went beyond simply rhyming in their own language; they invented dialects and words which remain unique to the French scene. “In the UK, you had the weight of American hip hop to live up to,” explains Zdar. “But here, people didn’t speak English, so naturally they rapped in French. If you go to a kid here who’s into hip hop, he’ll listen to 85% of French stuff. They have their own style, own language, everything.” The French hip hop scene may have introduced the cheap production methods which would fuel the French dance artists, but the direct link comes with three people who all worked at the same studios together – Philippe Zdar, Hubert ‘Boombass’ Blanc-Farancard and Etienne de Crecy. A trio who, in various combinations, would produce some of the most influential records. Pioneering releases that heralded the arrival of French Touch – La Funk Mob and Motorbass. The common figure in both outfits was Philippe Zdar.

Musique Concrete

An approach to music that would hugely influence the sampling generation and how they perceived music. Just as many people claim that everything is art, the musique concrete school believed everything to be a source of music. Through a combination of brilliant tape editing and imaginative musical structuring, these composers would create stunning pieces from the most wayward of sound

The concrete sounds they use are sounds from nature, industrial sounds, animal sounds etc., as well as strange sounds made by original synthesisers.

A style in which composition was based upon the acoustic manipulation of found sounds.

it was one music containing everything but, naturally, having recording as a medium. That is to say, music that will not be played but which will be inscribed on a medium. Recording is indispensable. I do not compose to be played; I compose in order to record and diffuse the music myself.

The Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrete created many of the recording techniques that would be adopted by rock musicians in search of the avant-garde sometime later. These included the Beatles, whose ‘Revolution #9’ from The White Album experimented greatly with cuts and loops. In the book Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now, John Lennon describes the creation of ‘Revolution #9’. “It has the basic rhythm of the original ‘Revolution’ going on with some twenty loops we put on, things from the archives of EMI. We were cutting up classical music and making different size loops, and then I got an engineer tape on which some test engineer was saying, ‘Number nine, number nine, number nine.’ all those different bits of sound and noises are all compiled. There were about ten machines with people holding pencils on the loops – some only inches long and some a yard long. I fed them all in and mixed them live

In the years that followed, Henry pioneered the use of the synthesizer (his first entirely synthesized project Le Voyage came in 1962), while also marrying the synth with a combination with found sounds and tape editing. Henry’s first major commercial success arrived in 1964 with his album Jerks Electronique which sold over 150,000 copies. In 1967 Henry combined forces with Michel Colombier to compose a piece entitled Messe Pour Le Temps Present for a ballet by Maurice Bejart. Henry commissioned Colombier “to recreate the sound textures and violent atmosphere of certain American films.” The resulting combination of Colombier’s psychedelic rock and Henry’s additional off-the-wall electronic effects has subsequently achieved legendary status and has been sampled heavily in recent years. The album has been described as a beat-heavy Moog masterpiece.

The legacy of the musique concrete and electroacoustic schools – both in the serious works of Schaeffer and Henry and in the humorous style of Perrey – is hugely important to all contemporary electronic and sampling artists. Not least of all in their home country where producers have taken many of the techniques and translated them to the contemporary setting. The editing systems are of particular note as they allowed people to understand the possibilities of manipulating sound sources. This translated to the sampling and sequencing technology as producers wilfully overrode certain limitations of the programme to forge new sounds.

French Touch

At this time, the first wave of the French Touch was also met with the media’s hunger for hype. And it was one press and promotions office that sold the hype to the editors – POP Promotions. They represented Motorbass, Dimitri from Paris (and the rest of Yellow Productions), Source Lab, Artefact, Pro-Zak Trax, and Versatile. Realising that most of their artists wouldn’t get column inches alone, the PR company started to sell Paris rather than the artists. The media bit and suddenly, journalists were hopping the channel to check out this new scene. Interest was subsequently high enough for other artists to get caught up in the growing hype. This coincided with a major change in the transport system that would have an enormous impact on the lives of English and French youth – the Eurostar. “I’m sure that Eurostar is a big part of the French Touch story,” confirms Pedro Winter. “The DJs started to go to London on Eurostar to buy records from Black Market and, in 1996, all of the record industry was chasing Daft Punk, meeting them in their offices. It meant that the industry was taking the Eurostar to talk about Frenchy music.” The next event was possibly the most important. Three excellent albums came out of Paris in two months: Motorbass’ Pansoul, Dimitri from Paris’ Sacrebleu and the Source Lab 2 compilation. Amazingly, all three albums were given the Album of the Month spot in Muzik. First came Dimitri from Paris and Source Lab in the same month, and then Motorbass. As a triumvirate, the albums suggested France was a hotbed of undiscovered talent. Suddenly the entire UK music industry went looking around the studios of Paris for their own slice of the hype. As these three were followed by similarly strong releases from Super Discount and producers like I:Cube, it then seemed impossible to avoid the French scene. As has been pointed out to me by numerous French producers, the UK press always referred to Paris as being France. With this hype came the major label interest, which brought a certain amount of power for the artists who were subsequently signed.

If the French Touch had had a positive effect on some people, it was perhaps predictable that techno DJ and producer Manu le Malin wasn’t enthused about it. “When French Touch came out, France was suddenly considered a house country, but this wasn’t really true,” he argued. “People thought we were all into filtered disco, but that was fucking rubbish. Laurent Garnier never did a filtered house track; he never played it. Ever. Fifteen years after he started and he’s still packing the Rex Club and he only plays serious music. No, the problem with that French Touch thing is that everyone outside of France thought that we were a house country. It took about a year and a half to get rid of the hype. “Also, because of the French Touch, some people were forced to go to Germany,” he added. “People like The Hacker, or Vitalic who would blow you away, man. He did a remix of one of my tracks because he wanted to do a hard track rather than a house track. And he made a fantastic tune for my label. Because there are the techno artists getting attention, all of a sudden, French Touch just disappeared. Now it’s just French artists. But they were forced to go to Germany to get noticed because no label would touch them here.” Ironically Manu’s last point may actually turn out to be one of the more positive aspects of the French Touch. It created a reaction among the more underground artists to forge a new sound. This would create the next wave of French electronic music.