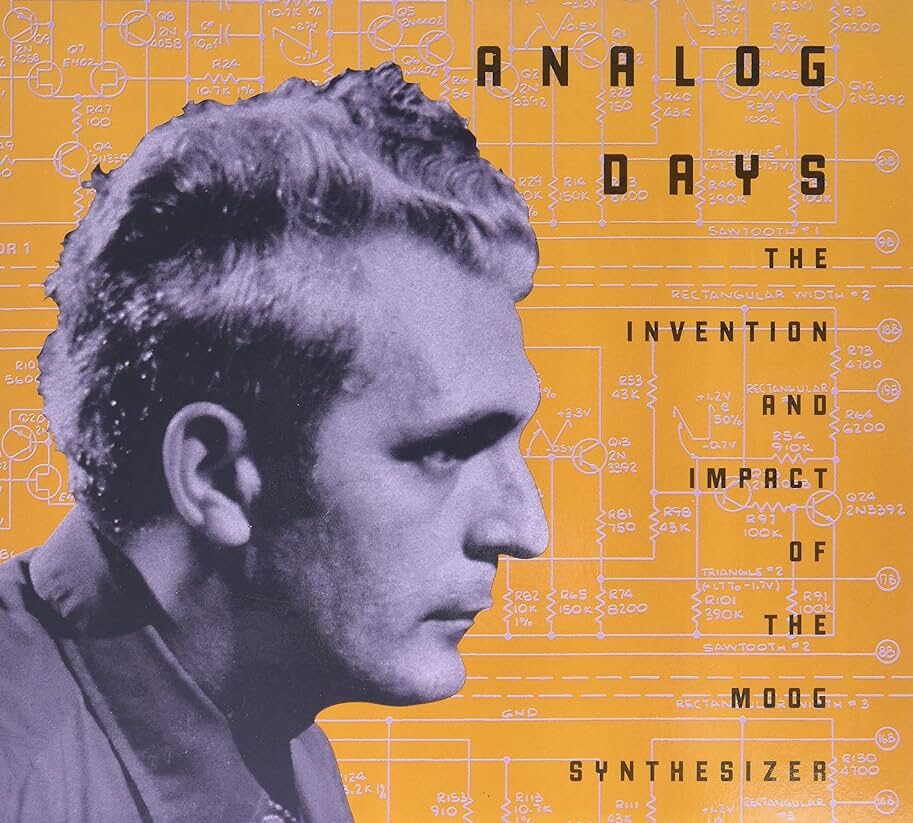

In the book, Pinch and Trocco trace the origins of the analog synthesizer with a focus on the different phases in its life; from its invention to its widespread use. Whereas Moog synthesizer is the central focus and core of the book, Buchla accompanies Moog’s story. The comparison between the synthesizers adds an analytic and explanatory power to the narrative of the book by showing how cultural and commercial factors translate into differences in technical ideas, their emergence, and development.

The development of modular synthesizers began in the early 1960s and was led by Robert Moog and Don Buchla. They both established separate synthesizer design traditions, one on the east coast and the other on the west coast of the US. Despite starting at the same time, their designs greatly differed from each other, and their synthesizers had unique sounds, which resulted in different types of music being produced with them. Moog synthesizer was designed to be more user-friendly as revealed by its conventional keyboard design whereas Buchla synthesizer relied on a series of touch-sensitive pads. In addition to the commercial viability of Moog as a user-friendly device, the triumph of Moog also owed to social factors such as the encounters of musicians and composers around Moog, including Herb Deutsch, Walter Sear, Bill Hemsath, Bernie Krause, Paul Beaver, Wendy Carlos, Keith Emerson, and so on. Moog entered the homes and studios of musicians, listened to what they wanted, and responded to their needs by refining the components of his synthesizer, which has been the most important factor in his success as claimed by the authors.

The book also mentions the impact of synthesizers on popular music and culture, including the use of Moogs by the Byrds and the Beatles, EMS synthesizers by European art and progressive rock bands, and ARP synthesizers in sci-fi movies. The book aims to connect technology and culture with a focus on machines and music coming together. It highlights the collaboration between engineers, musicians, and merchants and the interweaving of practices, discourses, and material artifacts in the production and consumption of sound and music as well as noise, and silence.

Spotify Playlist of the Book

Excerpts From the Book

On Roland Machines:

Many of today’s e-music groups, DJs, and remixers use analog synths, often along with digital samplers. Derrick May and Frankie Knuckles’ experiments with a Roland analog TR-909 drum machine is said to have led to techno and house music.48 Knuckles is reputed to have bought the Roland from May and used it to “segue between tracks and to crank up the sound of the bass kick at a crucial point in the song.” A whole generation of Roland analog bass and drum machines like the Roland TB-303 bass machine are core constituents of techno, and DJs and techno groups even name themselves after these early Roland machines. As one commentator notes: “Using drum computers marketed by Roland of Japan in the early eighties which by this time were obsolete, discontinued and available cheaply on the secondhand market, Chicago’s young hustlers wrenched out the possibilities that the manufacturers had never envisioned . . . their sizzle and boom locking into the mood of the clubs. Over a big sound system they reverberated through flesh and bone. This was do-it-yourself music; anyone could join in . . . you could just fire up your box and go” This is a sentiment that Dennis Houlihan, the president of Roland USA, would applaud. He once told us he wakes up each morning and says, “Thank God for rave!” pp. 322-323

Materials and Politics:

There were cheap war-surplus and industrial-surplus parts aplenty, and on the way home from school Bob would often stop by “Radio Row” (situated around Fulton, Dey, and Cortlandt streets) to pick up vacuum tubes and boxes of capacitors. His father would bring home scrap metal from work for making panels, chasses, and so on.

And it wasn’t just in America. In Britain it was the same. One of us (Pinch) bought his first short-wave receiver from a war-surplus store in a provincial city in the UK. It was an R1155 set that had been stripped from a Lancaster bomber and had the words “Eager Beaver” etched above the giant tuning dial on the front panel. This receiver could tune in all sorts of illicit stuff, like Radio Havana. p.13

If your interest was in making electronic sound effects, the surplus stuff was invaluable. Synthesizer pioneer Don Buchla told us how the San Francisco Tape Center, one of the main venues on the West Coast for making electronic music in the early 1960s, used war-surplus gun sights and test equipment. p. 14.

The Context of Buchla’s Invention

The 1960s was an opportune time to do new things. The space age was taking off, and electronic sounds had always been part of the mystique of space—the bleeps of the first Sputnik emerging from the background hiss of early radio receivers is etched into the Cold War consciousness. But space meant something else to synthesizer pioneers: it meant a source of employment. NASA needed engineers. Before founding the synthesizer company ARP, Alan Pearlman made equipment for NASA, and Don Buchla’s talent for electronics too soon found a new home in space.

Berkeley administered a number of NASA projects. Buchla took part in some of the first investigations of the Van Allen radiation belt in the magnetosphere above the earth’s atmosphere. He even directed a project to explore the feasibility of sending chimpanzees to Venus (conclusion: not feasible). He has worked on and off for NASA throughout his career. NASA contracts are one of the few forms of financial security available to the maverick synthesizer designer: “They don’t pay much, but they pay more than music . . . and it has been fascinating work.”

At NASA Buchla met and worked with the first generation of astronauts. This gave him an opportunity to explore an interest that stretched back to his childhood and that would obsess him the rest of his life: human–machine communication, “just a general interest in how man communicates with machines. I started it as an early child and it continues. And music brings out many of these problems.” pp. 33-34.

Wendy Carlos:

We would probably not have heard of the Moog synthesizer at all if it had not been for Wendy Carlos, who laboriously assembled electronic music in the studio and produced the sensational album Switched-On Bach (1968). This record made Moog and Carlos famous, was responsible for introducing many other musicians to the Moog, and led to a whole genre of “switched-on” records, including Switched-On Bacharach (1969), Switched-On Nashville (1970), and Switched-On Santa (1970). But rock and pop music was where the Moog synthesizer found its true home. p.8.

Other customers were important for the future of the synthesizer, and none more so than Wendy (formerly Walter) Carlos, who pushed Bob to perfect the technology. It was at her urging that Bob designed his first touch-sensitive keyboard. She also came up with the idea of adding the portamento control and the fixed filter bank (a form of graphic equalizer), which eventually became standard features. The portamento control, which allows the voltage generated by one key to slide smoothly to the next, was particularly important for live performance. It was rock performer Keith Emerson’s favorite feature of the Moog. pp.57-8.

Bob’s detailed knowledge of electronic musical instruments and Carlos’s own increasingly refined sense of what he wanted from the new medium made a perfect pair. Carlos, by reputation, was shy and intense, and this melded well with Bob’s own slightly unworldly personality. Carlos was also instrumental in helping Bob tweak his design for a touch-sensitive keyboard into a workable mechanism. Bob fully recognizes Carlos’s input into his project: “Yeah, and he—she—uh, was always, you know, criticizing— constructively criticizing—telling me what kind of knobs feel good and things about the sound, what kind of function she wanted.” p.136